The Dirty Details of Self-Publishing an Indie Tabletop Game

May 10th, 2016

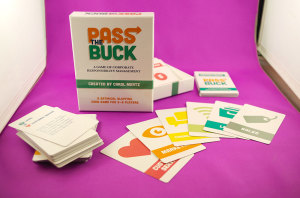

After spending more than two years designing, iterating, fundraising, and publishing my card game, Pass the Buck: A Game of Corporate Responsibility Management, I’ve got a lot of experiences to share that I hope will help to prepare other aspiring indie tabletop game publishers for the lengthy and arduous process. This will largely be a financial and production retrospective rather than a design postmortem (which I may write up another time). I’ll be totally transparent about the risks, costs, mistakes, and financial projections of self-publishing my first small-run indie tabletop game, so if talking about money, profit margins, and stupid mistakes makes you squirm, it’s time to get over it.

It’s important to note that none of the cost estimates in this include payment for my own time. I was self-employed full-time at Happy Badger Studio and Rampant Interactive, and was working on Pass the Buck: A Game of Corporate Responsibility Management as a side project in what time I had available. My studio partners were incredibly accommodating in that they were open to me spending a few studio hours per week on the game, and were willing to share their insight, feedback, and help during office hours. I do not mean to negate or devalue anyone’s working hours, but I do aim to primarily share what the documented hard costs of this project have been, regardless of undocumented working hours.

Design and Pre-Production

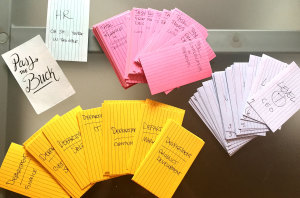

Early prototyping of tabletop games can and should be done relatively inexpensively, especially during the heavy iteration phase as you’re first testing the mechanics. I started out by scribbling card rules on cheap colored index cards, which was a nominal cost. For a board game, you can easily use things like cardboard boxes and scavenged materials from other games to keep the cost minimal.

Turns out most folks don’t like playing card games with shitty scribbled index cards, however, so once I got serious about playtesting, I knew I had to put together a nice-looking set of cards. The more polished the game looks, the more likely average playtesters are to take it seriously, so the deck needed to be designed and printed to give it a relatively finished look-and-feel.

I’m fortunate in that I knew I wanted to keep the visual design simple and non-illustrative (iconic and a bit boring, even, to drive the dry Corporate America satire home). Thanks to my straightforward artistic vision and experience working as a graphic designer, I didn’t need to hire an artist to help me design the cards and packaging; that’s potentially thousands of dollars that I didn’t spend because I took that job on myself. Keep the cost of art in mind if you’re designing a game that you’ll need to hire help for, and please don’t expect anyone to work for free.

I put together a Print & Play PDF to be compatible with perforated printable business card stock, which runs about $20 for a pack of 300. Pass The Buck’s prototype deck ranged between 90-120 double-sided cards depending on the version, so one $20 pack of cards was enough for me to print 2 sets (accounting for plenty of printer mistakes, which I was bountifully plagued with). A lot of designers use standard printer paper that they cut into poker-sized cards, then insert into plastic card sleeves. While sleeving lightweight paper cards may have been cheaper and simpler, I find sleeved cards awkward to play with, plus the business cards worked thematically with my corporate-centric game. I’m not sure how to estimate ink costs on this, but I printed a lot and ran through quite a bit of inkjet ink that probably cost as much as or more than the business card stock.

I decided after about a year of playtesting with the increasingly-grubby-looking business cards that it was time to get a real prototype copy made. I used The Game Crafter print-on-demand service, and ultimately purchased 6 prototype copies of various versions and box types, running me about $120 total for all 6 copies. These were the prototypes I photographed for the website, demoed with at events and conventions, and recorded the gameplay and pitch videos with.

Note for video-game-turned-tabletop-game-artists: don’t forget that print design is very different from digital. I was reminded of this the hard way during the print-on-demand phase. Pantone colors will be most accurate, but at the very least design in CMYK from the beginning rather than blindly converting from RGB. Maybe this seems like a really obvious step, but it was a dumb oversight I made that meant I was stuck with a couple of prototypes with inaccurate colors.

Estimated total hard costs for design & pre-production: $160ish (including best guess on ink and nominal costs)

Kickstarter / Fundraising

After playtesting, iterating, and polishing the game for over a year, I decided it was time to get serious about publishing Pass the Buck: A Game of Corporate Responsibility Management. My options, as I saw them, were to find a publisher, self-fund manufacturing, or fundraise. It’s not likely you’ll find a good publisher willing to take a risk on a first-time designer, and I wasn’t prepared to spend thousands of dollars on manufacturing costs, especially without having an idea of retail viability. I chose to fundraise on Kickstarter, where I’d get the financial help only if the game proved to have enough consumer interest to fully fund.

I started researching costs and planning the campaign in the summer of 2015, aiming for a fall 2015 Kickstarter launch. I spent some time breaking down what components of the game were necessary (106 basic bridge-sized cards and a cardboard tuckbox) and what would be nice to have (two-piece box upgrade, heavier cards, a booklet, a deck divider). This allowed me to both solidify a minimum quote request, and also have an idea of what components I could add or improve with stretch goals.

I sent out about a dozen quote requests for production runs that ranged between 500–5,000 decks, feeling I wasn’t independently equipped or prepared to distribute any more than that for my first game. The lowest cost of a run of 500 would be about $9 per game including freight costs from China, where a run of 1,500 would be about $5 per game including freight. The cost only dropped as low as $3 per game for much larger runs, so I figured I’d aim for 500 with a bare-minimum fund and 1,500 if I got a bit more financial breathing room.

After reviewing all the quotes, I chose to move forward with AdMagic, the company that manufactures Cards Against Humanity and Exploding Kittens. Their quote was straightforward and included fixed-cost freight in the base price, where some companies quote freight separately (if they orchestrate freight services at all), making the cost per deck seem low until you add in the additional thousands of dollars of international freight expenses. AdMagic also has experience working with new designers and Kickstarter projects, so I felt comfortable communicating honestly with them about my ignorance of the process and the flexibility I needed based on the as-yet unknown outcome of my Kickstarter campaign.

I knew that my minimum game cost would be about $4,500 for 500 decks, plus expenses for additional rewards (buttons and thank-you cards, estimated about $200), packaging (bubble mailers, plastic bags for buttons, mailing labels, and bubble wrap, estimated about $300), and postage (estimated about $3.50 for domestic packages and $14 for international, assuming the game would weigh less than 8oz). With these numbers in mind, I knew I’d need about $6,000 to produce and fulfill the bare minimum run, so adding a bit of safety buffer to that and accounting for the 10% of fees (5% to Kickstarter, 5% to credit card processors), I decided to set my Kickstarter goal at $7,500. I knew if I made any less than that, I couldn’t satisfactorily produce the quality of game I wanted to make, but I hoped to reach stretch goals that would help me to reach the 1,500 production copy goal so that I could ultimately produce higher quality games for less money. I set my stretch goals in $1,500 increments, so that the first stretch goal would allow me to produce 500 copies with a sturdy two-piece box, and the second stretch goal would allow me to produce 1,500 copies with the two-piece box and linen-finish cards. I was fortunate to reach the second stretch goal.

I DEFINITELY made these because mailing labels were thematically appropriate, not because they were dirt cheap. NO MA’AM. (Set of 10 sheets from the Dollar Store)

Hard costs for the Kickstarter campaign were pretty low. I used small printed mailing labels as handouts during game demos; I could easily stick these on my business cards or hand them out on their own. Between those and the simple signage I printed for public demos, the cost for campaign print collateral was probably about $20. I directed people to the game’s website before the campaign to learn more and sign up for the Kickstarter launch announcement newsletter, which cost about $30 annually for the web domain and hosting.

Let’s talk for a second about the work that I didn’t document hard costs for. I quickly slapped the game’s website together myself, thanks to more than a decade of web dev experience. Two of my studiomates and I worked together to take high-quality product photos and record a Kickstarter pitch video that I wrote myself. Four of us spent an afternoon recording a gameplay video. I spent a substantial amount of my own time editing the photos and videos for use in the campaign and on the website, using my limited college-level media production knowledge — if you don’t have the equipment or experience to produce acceptable photography, video, or web, you might need to budget in enough to pay someone to help out with this. I also put together the Kickstarter page well in advance, and had dozens of people review it and provide feedback in the weeks before the campaign kicked off. This gave me plenty of time to make changes and polish the campaign based on feedback from trusted friends and industry peers.

Using itch.io, I gave the Print & Play PDF to everyone who signed up for the Kickstarter launch newsletter before the campaign went live. After the campaign launched on September 23, I sent a P&P download code to every backer the moment they pledged, delivered via Kickstarter message. I firmly believe that showing backers that the game was in a complete enough state to play, enjoy, and provide feedback on helped to bolster my campaign. A number of backers increased from the base $1 P&P pledge to the full game once they played, and the P&P allowed for backers to share their excitement for the game with friends at board game nights around the world. It was a huge help; don’t underestimate the power of a good Print & Play.

I’d also like to note that I’m really happy with my decision to use itch.io as the P&P distribution platform. The flexibility and analytics were really useful to me as a creator, allowing me to track when codes were redeemed and how often the PDF was downloaded. While it was a bit more effort to send every backer an individual download code, I think it helped establish that the download was not a throwaway freebie, but that it had real value. I plan to keep the $5 Print & Play available indefinitely through itch.io.

It was great to demo at the IndieCade IndieXchange Game Tasting. Lots of wonderful, supportive folks played!

I traveled to two different game festivals during my Kickstarter campaign (Fantastic Arcade and IndieCade), the costs of which I won’t include with the campaign expenses since I went for fun and to represent my studio as a whole, rather than specifically for Pass the Buck: A Game of Corporate Responsibility Management. I did not purchase booth space. I did, however, end up with new backers from both events, most notably after being invited to demo for free at IndieCade’s IndieXchange Game Tasting event.

The value of traveling to these events is not negligible, but I don’t consider it a part of my direct campaign costs. If you’re wanting to factor travel in, though, you can estimate about $1,500 per event for travel and accommodations alone. Like I said, I didn’t pay for booth space, and I didn’t have to pay admission fees for either event. Ultimately, what was important about these events was getting to know new friends who were excited to help support the game, teaching new people how to play the game, and opening myself up to feedback from industry peers. I suggest that you start doing this locally by connecting with your local board game and game dev communities, and hosting as many demos as possible at public board game nights, game shops, and relevant events.

Estimated total hard costs during Kickstarter / fundraising: $50

Total raised by Kickstarter campaign: $11,280

Total cash received after Kickstarter fees: $10,161.29

As a side-note, my backup plan if the Kickstarter failed was to sell the game for $30 each through The Game Crafter’s print-on-demand retail shop. It would have been expensive for customers to purchase a game of prototype print quality, but it would have given me a last-ditch option for limited distribution with about $5 profit per deck sold.

Manufacturing

Now’s when we start really spending that cash. Shortly after the campaign ended, I signed a contract with AdMagic to produce 1,500 copies of a 106-card 300GSM blue-core linen-finish deck with a glossy two-piece box sized to fit. To save money and box space, the rules were printed on cards instead of a rulebook. That production run, including an optional $200 sheet proof, set me back $7,415. (Disclaimer: this pricing is contextual and time-sensitive, so I can’t speak for the manufacturer or guarantee that they can or would still offer the same pricing for similar game components.)

In order to sell the game in retail outlets, the game needed a unique UPC code included in the packaging design. I bought 5 codes from a UPC reseller for $15 total because for some reason it seemed like a good idea to have extras laying around. I don’t know, stuff gets overwhelming sometimes and I like to be over-prepared. I only needed one.

My team and I subjected the sheet proof to rigorous examination. According to my cat, it smelled sorta weird. I concur. It didn’t taste great, either.

The campaign ended on October 28, so I’d originally expected to submit the final art sometime in mid-November or early December. Unfortunately I saw a bit of a delay due to the inclusion of about a dozen backer-written tasks in the final game; a couple of folks took longer to write their task than I had anticipated, so I didn’t actually get the ball rolling on production until mid-December. This meant I didn’t get the pre-production sheet proof until early January.

I took a few days to review the sheet proof before approving in mid-January (it’s the last chance to catch errors or mistakes before small changes mean big additional production cost, so it’s better not to rush it). Manufacturing took about a month and a half after that, and I received the complete production sample on March 1st. I was obnoxiously thrilled to see that the production version included a cardboard deck divider which wasn’t included in the base quote. In a flurry of excitement, I approved the production sample immediately, the games went into assembly, and I was given an estimated shipping date of March 14.

It takes about a month after the shipping date for the freight to travel from China to America, then it takes another week or so in customs and freight forwarding. I got word that the games were in my city and ready for delivery on April 22, and received the freight at my studio in St. Louis on April 26. The near half-ton of games came on a pallet as thirty 26-lb boxes, packaged in cases of 50 games each.

I estimated the May 2016 fulfillment timeline for the Kickstarter campaign based on the manufacturer’s maximum time estimates, plus an extra month to accommodate for Chinese New Year and any unexpected setbacks. I was incredibly relieved that the games arrived just in time to meet the “very conservative” May 2016 fulfillment estimate, even with no changes made during production and all immediate sample approvals. I’d quietly hoped to have the games in my possession in March. The lesson here is that you should always assume things will take a lot more time than you expect them to, even if everything goes according to plan.

I’d also like to note that, because this was my first time facilitating any production of this scale and was unfamiliar with the process, I was apprehensive to ask for changes. While I’m very happy with the quality of the games, there are little things that I see now that I wish I’d have changed before the full production run. It’s all very minor, but it feels a bit less so knowing that the problems I see are emblazoned on 1,500 copies of the game forever.

Total hard costs for manufacturing and freight: $7,430

Kickstarter Fulfillment

The Kickstarter campaign had a few higher-pledge reward tiers that included buttons ($160 for 150 sets of 6 1” buttons) and thank-you cards ($60 for 100 4”x6” specialty postcards), as well as autographed games and early prototypes. These were rewards that I knew would be relatively low cost and low effort on my part, but would provide tangible opportunities for folks to chip in for more if they wanted to help support the game’s production. Also, who doesn’t love collectibles?

It was because of these extra personalized rewards that I opted to do all the Kickstarter fulfillment myself, rather than using a third-party fulfillment service. I purchased 400 8.5” x 12” poly bubble mailers ($145), small plastic bags to package the button sets ($7), 400 printable shipping labels ($18), and bubble wrap ($15).

I hosted a backer reward “pick-up-and-drink-up” meetup at a favorite local bar, where I invited local backers to come get their rewards, chat about the campaign, and get their games autographed. This worked out really well, was a lot of fun, and spared me shipping costs on more than 40 rewards. Plus, it scored me a couple free beers. CHA-CHING!

Using a combination of stamps.com and paypal.com for postage, I stumbled into a bevy of problems during fulfillment, and became more burned out than any other phase of production. Printing postage yourself means you’re vulnerable to printer errors, user errors, hardware restrictions, and software bugs. It took a lot more effort and emotional energy than I had anticipated, although I’m sure it was still heaps easier to prepay and print than trying to send 300+ packages the old-fashioned way.

The studio became a disaster area during fulfillment. If I was doing this at home, my cat would’ve peed in every one of those boxes.

The base reward of one game inside the bubble mailer weighed in at 8.3oz, and increased to 8.8oz with the additional buttons and note. This was lightweight enough that I could send the US-based packages for $3.30 each via First Class mail. Backers who pledged for multiple copies of the game required Priority Mail service for packages over 1lb, which cost as much as $10 per shipment.

I ran into a problem with International shipping, though, in that I’d originally assumed the game would weigh less than 8oz. Turns out that when you go from 8oz to 8.1oz, USPS’s First Class International package rate increases from about $14 per package to about $22. With 43 international backers, this meant I was looking at an increased cost of more than $300 for a less-than-one-ounce overage. It wasn’t the end of the world thanks to the generosity of so many backers, but it was frustrating and disheartening to have such a substantial cost difference sneak up on me.

Total cost of additional rewards and shipping supplies: $185

Total cost of domestic postage: $770

Total cost of international postage: $890

Retail Distribution and The Future

This photo shoot would have gone A LOT better if I’d remembered to bring a flash and diffuser. That’s what Photoshop’s for, right?

For the sake of time, simplicity, and independence, I’m using Amazon Fulfillment Services as my primary method of distribution. I took new product photos of the retail-ready game and completed an Amazon product page, then shipped 18 total cases (900 games) to various fulfillment centers around the United States. That shipment only cost about $175, thanks to Amazon’s discounted shipping partnerships.

After some serious decision fatigue, I set the game’s MSRP at $20 (Jamey Stegmaier has a good blog reflecting on board game MSRP that, coupled with a lot of market research and self-reflection, helped me come to my decision). After fees and shipping, I get about $13 of every sale. If I never discount the game and manage to miraculously sell every copy, that means at the most, I might make $11,700 from those 900 games. (If that sounds like a lot to you, hang on tight for the “Real Talk” section below.)

After fulfilling Kickstarter rewards and stocking Amazon fulfillment centers, I’m left with just over 200 games to use at my discretion. I can sell these at conventions for full MSRP, send them to press outlets (exchanging the cost of the game + shipping for the possibility of valuable feedback or a review that could catalyze sales), or try to sell them wholesale (which, as my own publisher/distributor, I’ve set at 50% of MSRP) to game shops that may be willing to risk stocking a game by an unknown, first-time indie designer. So, at most I stand to make $2,000 from the games that I still have in-hand, only if I can figure out how to sell every single copy myself for full MSRP.

Amazon does charge a small monthly inventory storage fee for warehouse storage space by the cubic foot, and then a substantial amount more for “long-term storage” if you can’t move your product quickly enough. If I can’t sell a bulk of the games within 6-12 months, those long-term warehousing fees could start to get disproportionate to the amount of profit made from the games. If sales are looking grim, I’ll need to pay to have the games returned to me, at which point I’d be forced to figure out a different storage and distribution solution that will undoubtedly require a lot more effort on my part. All I can do is hope it doesn’t get to that point, and do my best to sell what’s on Amazon while it’s there.

Cost of shipping to distributor: $175

Cost of warehouse space: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ?

Profit from game sales:¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ?

Total hard cost of small-run game production to-date: $9660

Production and fulfillment only left me with about $500 remaining from Kickstarter, which is close to what was paid in taxes on the $2500ish of unallocated Kickstarter profit at the end of 2015, even though I was careful to purchase and write off as much of what I needed as possible before the year’s end. I’m fortunate that the project remained within budget, as a lot of Kickstarter projects end up underestimating additional costs and result in substantial out-of-pocket expenses for the creator.

I would like to reiterate, however, that the money made from the Kickstarter did not cover any working hours spent on the game, whether they were my own or those of my studiomates, and I did not have to pay anyone for artwork or consulting in any capacity.

Real talk

Let’s say as an independent game designer living in the midwest, I expect to earn a very modest annual salary of $30,000 — if I sell every single game I sent to Amazon and make that $11,700 in a timely fashion, it barely covers 4 months of my time. Not to mention that if I use that money as a salary rather than earmarking it for a reprint, the game would be sold out forever with no hope of a reprint. (BONUS: don’t forget the hefty self-employment tax on my earnings.)

Let’s think idealistically for a moment, and assume I want to use the money to reprint the game rather than take a salary from it (which happens to be the case). In the unlikely event that I make the absolute maximum amount possible from the remaining game sales ($11,700+$2,000, between Amazon and my remaining stragglers), even before taxes and monthly warehousing fees, that wouldn’t be quite enough to cover a second print run of 5,000 copies at $15,000. If it gets to that point, I would need to either opt for a smaller print run or invest additional personal funds to produce the full run of 5,000 games. Let’s say I completely sold out of a run of 5,000 through Amazon, however — in that case, I would be more likely to find myself with a year’s worth of modest salary plus the ability to re-order another print run. That scenario is very unlikely and hinges on extraordinary retail sales, but it might give you an idea of what it could take to live off of a single tabletop game’s sales.

I don’t have enough experience with retail sales to know what a realistic outlook is, but I do know that I won’t likely be living off of card game sales anytime soon. Fortunately, my goal from the beginning has simply been to see my idea come to life, allow people to play and enjoy the game, and experience the process of publishing a physical product; I had little-to-no expectations of sustainable profit. My hope is that Pass the Buck: A Game of Corporate Responsibility Management sells enough copies that I can pay to order a second production run and keep the game alive and available for sale. Should I continue to focus on tabletop games, release several more titles, and hone my skills as a designer, publisher, and distributor, it could prove to become a much more sustainable business model. In the meantime, I’m infinitely grateful to have had the opportunity to publish and distribute my first tabletop game without major financial risk. Who knows what’s in store for the future.

TL;DR: If you plan to self-publish a small-run independent tabletop game for the first time, plan to put in a lot of effort for very little (or no) financial return.

Hey Carol,

Thanks for this write-up. It’s great to see someone publishing for passion of board games, and being up-front about the financial risks involved. It gives me inspiration as a hobbyist designer that maybe one day I can publish one of my own designs, and maybe even break even.

I recognized you as a regular contributor to the St. Louis Game Co-Op, and have listened to some of your lectures on-line. I wish that there was a resource like this available in Springfield. I’m sure there are others in our city that would appreciate this as well. I’d like to come to one of the St. Louis meet-ups sometime but driving 6 hours round trip is hard to manage, especially when most events are on week days.

If you could take 10 minutes and give me a brief, honest critique of the few prototype designs I have listed on my webpage at http://xyvir-games.tumblr.com/catalog, I would appreciate it very, very much. I’m most interested in feedback concerning which single design seems the most publish-worthy and marketable, if any. It’s often hard for me to see past my own bias.

Thanks once again for this article and insight into the world of self-publishing. I hope at some point you do write that design postmortem, as I’d be interested in reading that as well.

-Tyler

Hey Tyler! Thanks for reading, and for the kind comments. Sorry it’s so out of the way for you to get to St. Louis for our local events; maybe you can at least come for PixelPop Festival this year! Will you be coming in for Geekway to the West?

Your designs all look very cool. It’s hard to determine which games would be most worth pursuing without playing; have you had much opportunity to playtest with different audiences? I’d expect you’d get some great insight as to which game goes over well and excites players at large if you find a handful of playtesting groups who are willing to play a few times and provide you feedback about what does/doesn’t work, and what interests them most about each design.

Best of luck!

I appreciate your honest review of the process. We are sort of encountering the same thing for our game. We raised a bit over $20k, but had artwork costs and other fees that crippled any potential profit we could make. after everything we will probably have about $1,500 extra after manufacturing for marketing and I personally took $1,500 as I don’t have another job and needed to live for a few months (I can live super duper cheap). So in total after Kickstarter fees we got around $17,700 and made roughly $3,000 in profit if nothing changes from now until fulfillment (fingers crossed). We developed the game super fast, but even still we have a team of people who don’t stand to make any salary for an extended period of time.

Wow, that’s a very sobering prospect; it’s great that you were able to develop it so quickly to avoid too many unexpected costs. Hopefully you saved some for shipping and fulfillment too! In spite of my research, I was still surprised at how much time and money fulfillment took. I hope you have the best of luck with your studio and game!

Great article. Sounds eerily familiar to my experience publishing “Mr. Game!”, right down to the manufacturer of choice: AdMagic. They’re great, aren’t they? And being your own artist is the only way to go. I have no idea how non-artists are able to self-publish games on a reasonable budget…

I empathized with your point about being more bold when asking for changes to the product. One of the pieces in my game is pink instead of purple, and it’s killing me. But at the time, I was running late to get games to backers anyway, and I didn’t mention it to the plant. I regret that now!

I see you saved a lot of money shipping the games yourself, and I wonder if I made a mistake using a service. But ShipNaked (my fulfiller) is doubling as a warehouse to ship games from, so it’s been alright so far.

Please keep chronicling your efforts, especially if Pass The Buck makes it into a brick-and-mortar store. I haven’t been able to pull that off yet (not even at the bookstore of my alma mater) and I am dying for some good advice.

~Frank

I did enjoy working with AdMagic; they were really easy to communicate with, and the final product is really solid.

I actually got Pass the Buck into a brick-and-mortar store the night of the pick-up-and-drink-up, but I didn’t include it in the article because it was totally by chance and I didn’t think it would be particularly helpful to include. The bartender (a friend of mine) knew a guy who runs a local comic book shop, and told him about the backer pickup event. The shop owner came by to check out the game, then bought two copies wholesale and put it on the shelf that night!

I’ve talked to a couple of other local shop managers who have shown interest, but I have yet to follow up since getting the game in-hand (other life things are keeping me pretty occupied right now). I know folks who’ve had luck by just chatting with owners and managers of small locally-owned shops. They don’t typically buy many copies—especially from unknown designers—but 1-3 copies is better than none at all!

I hope to do a follow-up article once I figure out retail distribution a bit better, so that I can hopefully demystify that process a bit too. I’ve still got work to do just to demystify it for myself first, though.

Carol,

Thanks so much for doing this; this is great information. I subscribe to Jamey’s blog and it is really interesting and helpful as well. I dabble in game design and would love to see one of my games published some day. Do you have a spreadsheet with all of these costs laid out? Could I get a copy of that? Also, did you do any advertising on BGG before or during your kickstarter campaign and if so, do you think it was worth it, and if not, why not?

Thanks again!

Gordon

[…] Pass The Buck – Carol Mertz breaks down the financial cost of her card game in great detail, along with links to the resources she used to prototype and print the game. […]

Hello Carol,

I apologize for coming across this post so late but I was interested in how you came to the decision to ship 900 copies to Amazon? Was there some kind of cost benefit from shipping so many copies all at once?

Thank you for sharing so much detailed information about your experience. Very insightful for the small publisher.

James

No cost benefit to my knowledge; I foolishly decided at the time that I wanted to use Amazon as my primary warehousing solution. I discovered too late that it was a bad idea to do that, not only because it didn’t end up being the easiest way to sell games, but also because they charge a high long-term storage fee after your product has been there for >6mos. Since my games were moving so slowly, they recently offered me a deal to recall the majority of my games, so I had them return 700 copies to me (and perhaps even that wasn’t enough to satisfy them). I now know what it’s like to receive freight to a residence — there’s now almost 1,000 games in my apartment’s coat closet!

Fascinating read. Quite eye opening to someone who is curious about doing what you did. Thank you for posting this.

If you don’t mind my asking, how would you say its worked out since you started and would you do anything differently?

Thanks

Nathan

[…] is an excellent write-up about fulfilling a Kickstarter campaign by Carol Mertz. She had extra reward items like buttons that were cheap to produce but had a high perceived value […]

This is a great write up. I think I am on the right track. It has helped me see that doing your own art work as well as manufacturing yourself is the best way to go. I’m glad I am able to go down that route. Right now I’m envisioning selling my game for about $50 msrp. It will cost me around $11 total to make and ship each unit.

I know you have moved on to other game designs, but do you have a status update on the selling of this game? Were you able to sell all of your remaining stock? How many games are you left with? What was your overall profit?

Hey Glenn! Thanks for following up. Unfortunately I’ve been pretty bad about keeping close tabs on my inventory and sales since about 2017, but I can provide a little more detail.

The rough timeline is that I pulled PTB from Amazon in 2018 because the warehousing costs were more than the sales I was making — that was my only retail outlet, so the game was just unavailable from 2018-2021. I occasionally self-fulfilled a few copies on request, but I did not offer an active DTC sales channel. I also moved across the country twice (in 2017 and 2019), so I had to unload a lot of extra stock for free in some cases, donating copies to NYU, offering copies to classmates as I was leaving their Master’s program in 2019, etc. In 2021, I was approached by my friends at Gather Round Games, who were exploring indie distribution, so I agreed to team up and see what happened. They connected me to a couple of hobby shops, but otherwise their online store has been the sole retail outlet for the physical version since last year, with only one case in stock. The remaining cases are jammed into all corners of my apartment, probably totaling around 300 copies, maybe more—I haven’t taken inventory in a long time.

I would consider this a break-even project, at best. The profit has been negligible, and has most certainly not covered the time I’ve spent on the game, much less the storage costs while I was in NYC for grad school. It was a great experiment and a wonderful learning opportunity, but I’ve discovered since that there are not very many instances where self-publishing physical goods can turn enough of a profit to be sustainable.

For what it’s worth, I would never self-publish a tabletop project again — this experience convinced me to only work through publishers moving forward. I work for a big mass-market publisher now, so I’m getting A LOT of insight into the processes, and am consistently blown away at how much work goes into making a game profitable! An experienced publisher will always be MUCH better equipped to handle production, sales, marketing, and logistics than I could ever be on my own.